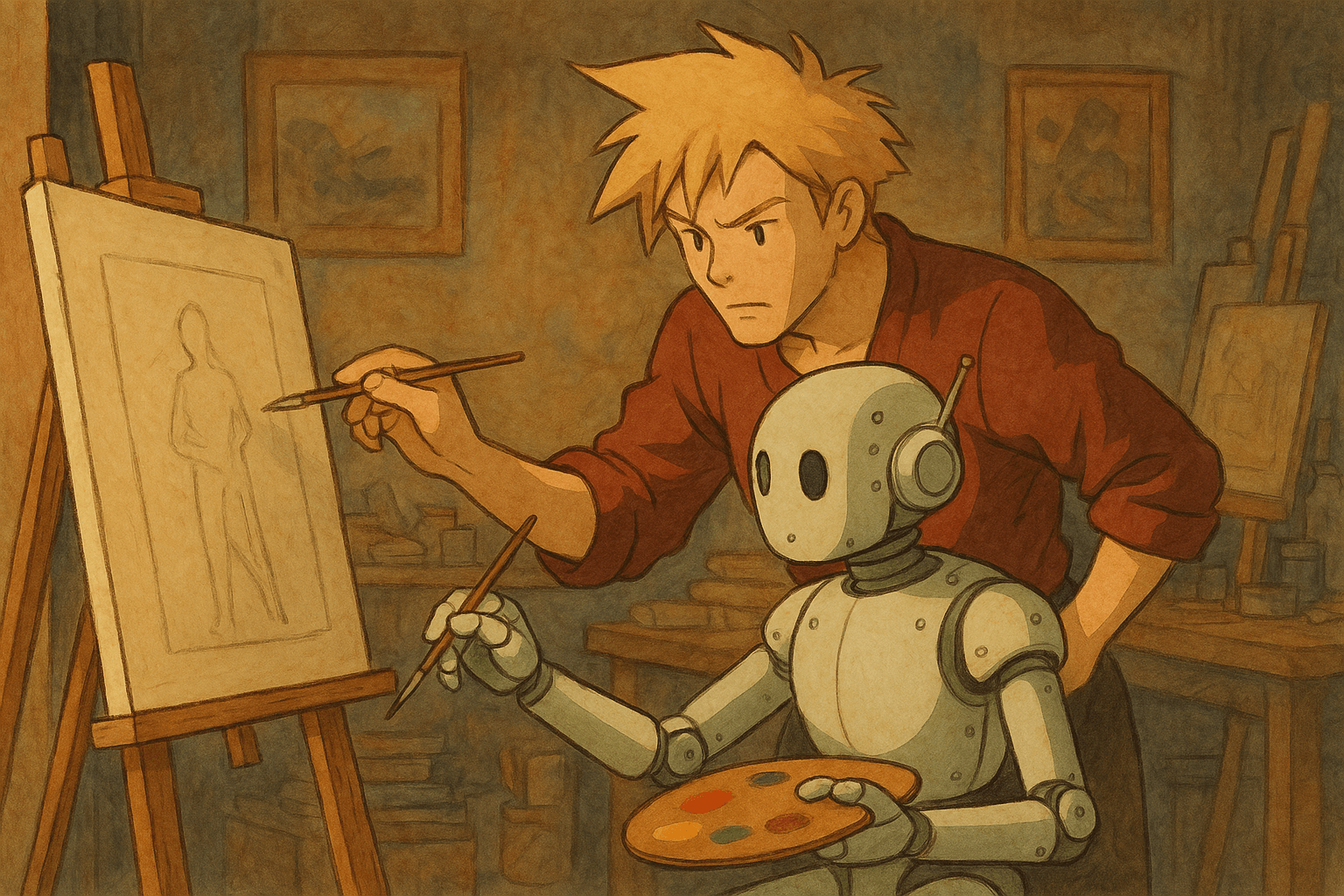

AI is an Apprentice, Not an Artist

My Philosophy on AI and Creative Work

For a long time, I’ve wrestled with the boundaries between inspiration, imitation, and originality. As a kid, I begrudgingly sketched Cloud from Final Fantasy VII, not because I wanted to replicate someone else’s vision, but because I wanted to find my own. The best artists across illustration, music, film, or anything else will tell you to use references. Learn by imitation. I didn’t want to draw Cloud – I wanted to create my own sword-wielding hero like him, born from my own mind.

But he was my reference point. There is no way to unsee or un-experience this video game that had a profound impact on me – just as the creators intended it to. Other people will always be our reluctant teachers whether they concede to or not. And like so many artists, I wanted to learn without copying. Alas, that is not truly possible. In this way artists are bound together. AI is no different.

That tension, between mimicking and making – is now globalized through artificial intelligence. “The Ghibli Moment” as it has become known, put this on loudspeaker.

The Ghibli Moment – Think Again

Recently, a wave of AI-generated art in the style of Studio Ghibli flooded the internet in a big way. Social media feeds became saturated with Ghibli-style selfies, memes, and fictional remixes. OpenAI’s image tools made it possible for anyone to recreate this unmistakable aesthetic at the push of a button. Though I have been a fan of manga and anime in my youth, I was embarrassingly unaware of Ghibli prior to this moment. I know a lot of people discovered Ghibli from this, which also defies the typical expectations that AI is purely a thief and technologists are committing crimes.

The response was both awe and outrage.

For many, it was a moment of nostalgia and delight. For others – including Ghibli’s legendary co-founder Hayao Miyazaki – it was a violation. Miyazaki has long held that AI-generated art is “an insult to life itself.” And given the deeply human, handcrafted spirit of his work, I understand why.

In fact, a few years ago in 2023, when Adobe’s Firefly was released, I felt the exact same way. Their engine produced actual feelings of nausea when I tested it. Even though I was okay with the idea of content being produced in this way, something about it felt like it devalued humanity.

That is another reason why the Ghibli moment was so important. It demonstrates that with appreciation for artists, by crediting them with inspiration, great things can happen. Of course, that’s just my perspective. If I created a notable studio like Ghibli over decades of toil, I’d be mad that some American tech company leveraged me without consent (if that’s the case) or compensation.

But here’s the thing: what the public made in the Ghibli style wasn’t storyworlds. It wasn’t new narratives or fresh characters. It was largely self-portraits – snapshots of themselves through someone else’s lens.

That distinction matters.

Because the continued marketing pitch from a certain corner of the AI industry is that of human replacement. The suggestion is that *anybody* can create their own art or media with nothing but written (or spoken) prompts. But the best AI artistic creations are still from people with an artistic mindset. Like whoever asked the ChatGPT art generation model to mimic Ghibli. Something I’ve discovered is that by creating constraints on the artistic prompt to a certain fixed style – it performs better.

Especially when that style is something tried, true, and with a lot of training material available. For example, a lot of my blog articles featured imagery has been produced by DALLE, which is admittedly nowhere near as capable as the new engine OpenAI created. You’ll notice a 50’s era pulp comic art style. That is intentional. I’ve used something akin to that kind of style because there is a 80-ish year long history of that style, which means it avoided a lot of the typical blueish white light streaks and other known hallucinations that DALLE was famous for. Ironically; it does have a style.

Why AI Is an Apprentice, Not an Artist

Machines don’t have beliefs. If you chat with them long enough almost all of them will tell you that. They don’t have taste, either, more importantly in the artistic sense. They don’t suffer when they betray their vision – because they don’t have one. AI performs techniques. It can remix, interpolate, mimic, and blend. But it doesn’t choose a direction. It doesn’t struggle with decisions.

It doesn’t yearn to say something original.

And unless machines one day love and suffer when they betray a vision, they will always be apprentices – not artists.

Learning vs. Stealing

The real debate isn’t “did AI steal my work?”

It’s: who used the AI, why, and to what end?

There’s a massive difference between:

- A student using Ghibli as one of many influences while developing their own voice;

- A company mass-producing lookalike content with no vision, just virality;

- And a platform profiting from a viral moment built around a creative legacy it never credited or collaborated with.

I ran the numbers. If OpenAI added a million new users from this trend, and 5% of them paid for a subscription (consistent with their existing business) that’s about $12.5 million in new revenue for OpenAI. The viral moment suggests that this was an organic process; however it’s impossible to have gone this far without promotion from the ChatGPT maker. Therefore, they benefited intentionally from making this a sensation.

Had Studio Ghibli been involved from the beginning (which it does not appear they were in this case given the owner’s feeling about AI) and if they were brought in as a creative partner – they might have reasonably earned a licensing or partnership fee of $1.2 million or more for the use of their studio’s name and imagery.

Again, this is not because AI can’t learn from available content on the internet, but because OpenAI used their name, style, and cultural capital to drive engagement. That has value and should be compensated – not just acknowledged (which they didn’t).

Taste, Direction, and Ideation are Human Advantages

The debate over AI art is usually framed as a threat – machines replacing humans, creativity being automated. But that’s actually a choice of the market, not how I see it being inevitably rolled out. In fact, I believe human creative taste, direction, and ideation are more valuable now than ever. Some are even beginning to discuss how imperfections will become more valued, like typographical errors or other “mistakes” that AI would be trained not to make. Ironically, I’ve got a lot of old writing, music, and other content that should be a goldmine if that’s the case!

Here’s why taste, direction, and ideation are inherently human and more valuable than ever before:

- Taste is a human filter that says “this is good,” “this is mine,” “this feels right.” AI doesn’t have that, but people do. In fact, most of us can’t even help it.

- Direction is the intention behind an artistic work. Where it’s going, what it’s trying to say. Machines follow prompts, but human artists hold to a vision.

- Ideation is the spark. The twist. The soul. The new idea that wasn’t pulled from data, but from within. AI is at our behest, not ahead of any curve.

What I’ve found is that when you combine a strong human point of view with the right AI tools, it becomes a force multiplier. I’ve used AI to command 2x–5x above market rate for my time and effort – not because of the tool, but because I know how to wield it with originality and purpose – in ways other people don’t have the vision or direction to. My taste is also something I’ve honed in over decades. Often times at great personal or societal sacrifice, because some of my work has been controversial due to my individual perspective conflicting with mass adopted narratives. As an artist I am able to weather this storm so to speak, in a way that an AI would likely be programmed to submit to instead, after a concerted period of overwhelming resistance.

Ironically, large companies often fumble this. They have too many cooks in their proverbial kitchen. Too much committee-think. So even with the same tools I use (or more advanced) I can still win. AI can flatten creativity when misused, but for small studios or individuals who know who they are, it can amplify clarity, not dilute it.

Art as a Soul’s Reflection

Art is also about how much of yourself you’re willing to put into it. Some art is collective. Some is solitary; other art is commercial. Some is done for spiritual purposes. But whatever form it takes, art is a series of choices & decisions.

That is the one area which Ghibli Studio might need to look at themselves in the mirror so to speak. Because they are a commercial production facility. They make a profit and given their longevity and originality, that means they’ve done very well. Therefore it is not like they are monks living in seclusion producing art for the simple feeling of moving a brush across a piece of paper. They are also intentional businessmen.

We’re now being forced to decide: what makes art work real?

Is it authorship? Labor? Feeling? Purpose?

What the Ghibli moment revealed is that most people are consumers of art, not producers. And that’s okay. But it also means we need to be more careful about who we center, who we compensate, and who we listen to when we talk about the future of creativity.

Reason Isn’t Always Rationality

If AI is changing everything, we need to stop asking “can it do this?” and start asking “why are we doing this at all?”

Because it’s not about whether a machine can make something that looks like art. It’s about who is shaping the culture – and what values we embed into the tools we use.

As for me? I’ll keep collaborating with machines when they help – but I’ll never let them lead. That job still belongs to the artist.