Beyond Left Wing and Right Wing Political Ideologies

Left wing and right wing thinking no longer serves anybody. Political discourse today is mired in oversimplification. Terms like “left-wing” and “right-wing” dominate conversations, reducing the complexity of beliefs and policies into binaries that fail to capture the nuance of modern ideologies. While these labels offer convenience, they do more harm than good, creating division, misunderstanding, and unproductive debates.

This oversimplification is not just misleading—it’s dangerous. By mislabeling or overgeneralizing political ideologies, we lose the ability to critically evaluate leaders, policies, and even our own beliefs. Worse yet, we risk falling into the traps of authoritarian figures who exploit these flawed categorizations to consolidate power. To navigate these complexities, we need a better framework—one that recognizes the multidimensional nature of political ideologies and helps us better understand ourselves, our leaders, and our societies.

Why “Left” and “Right” Are No Longer Useful Political Terms

The origins of the left-right political spectrum date back to the French Revolution, where those who supported revolutionary change sat on the left side of the National Assembly, while those loyal to the monarchy sat on the right. Over time, this binary has persisted, albeit in forms far removed from its original context. Today, people use these terms to lump together broad sets of beliefs: progressivism, socialism, or liberalism on the left; conservatism, capitalism, or nationalism on the right.

The problem? These labels fail to account for the nuances of modern politics. Take Adolf Hitler, for example. He is often labeled as “far-right” due to his nationalist and hierarchical ideology, yet his economic policies included elements of socialism. Similarly, Franklin D. Roosevelt is frequently described as “left-wing” for his New Deal policies, but his leadership style centralized significant authority in the federal government. These figures don’t fit neatly into a single axis, and trying to force them into one obscures more than it reveals.

Modern usage of “left” and “right” also fuels tribalism. People weaponize these terms to discredit opponents without engaging in meaningful dialogue. Instead of addressing specific issues or solutions, we’ve reduced discourse to choosing sides in an imagined tug-of-war. This approach blinds us to the complexity of political thought and leaves us ill-equipped to address the real challenges we face.

A New Framework for Political Ideologies

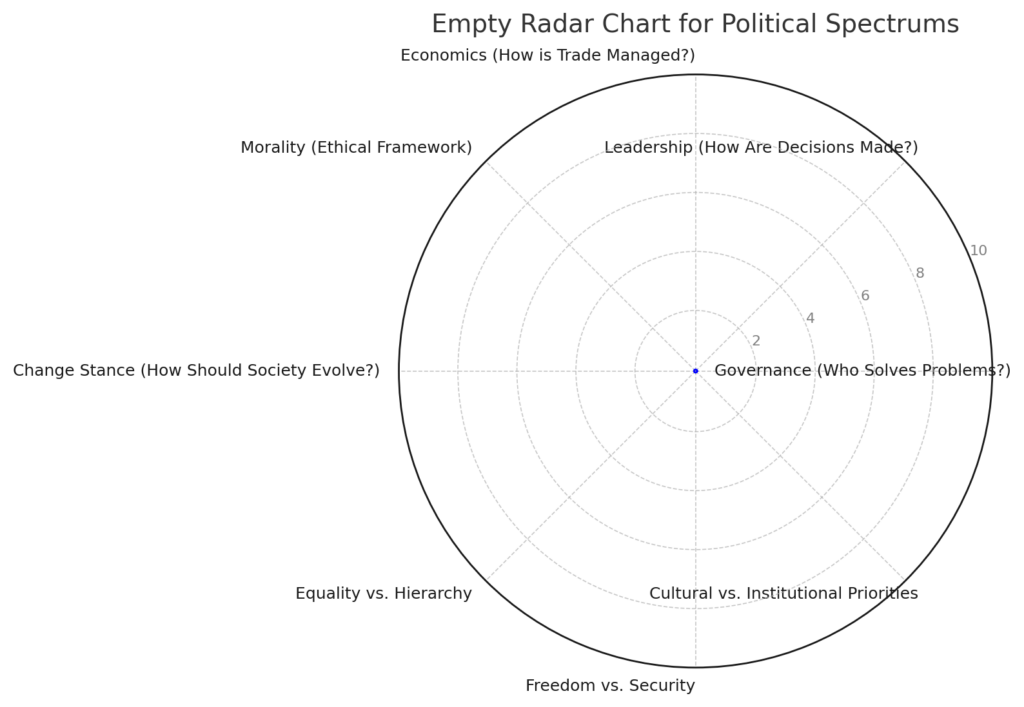

To move beyond this binary, I propose a new model based on five axes that better reflect the dimensions of political thought. These categories allow us to understand ideologies not as linear positions, but as multidimensional frameworks.

1. Governance (Who Solves Problems?)

This axis considers how much responsibility individuals, local communities, states, or nations have in solving societal issues. It spans:

- Individual Responsibility (libertarianism): Problems are best solved by individuals or small communities.

- Local/State Governance (republicanism): Authority rests with states or smaller governing bodies.

- Federal Authority (federalism): The national government should take the lead.

- Global Governance (globalism): International cooperation is necessary to solve problems.

2. Leadership (How Are Decisions Made?)

This axis measures the centralization of decision-making:

- Direct Democracy: Decisions are made collectively by the people.

- Republican Oligarchy: Representatives act on behalf of the people.

- Authoritarian Leadership: A single leader or small group makes all key decisions.

3. Economics (How is Trade Managed?)

Economic ideologies fall along a spectrum from complete freedom to state control:

- Barter Trade: Decentralized, informal trade without a formal currency.

- Capitalism: Trade and production are privately managed and profit-driven.

- Command Economy: The state controls trade and production, often under socialism or communism.

4. Morality (Ethical Orientation)

This axis reflects how much moral principles influence political decisions:

- Amoral Pragmatism: Decisions prioritize outcomes over ethics.

- Moral Universality: Decisions prioritize universal ethics and principles.

5. Change Stance (Adaptability to Change)

How much change a leader or society supports:

- Ultra-Conservatism: Focus on preserving the status quo.

- Incremental Reform: Change occurs slowly and methodically.

- Revolutionary Change: Major, rapid shifts to existing systems.

Why the Spider Chart Works

A spider chart, also known as a radar chart, maps these axes visually, offering a better representation of ideological positions than the left-right spectrum. Each axis shows where a leader or individual stands, creating a nuanced “shape” of their beliefs.

Strengths of the Model

- Multidimensional: Captures complexity by plotting multiple axes.

- Flexibility: Allows for comparison across ideologies, individuals, and contexts.

- Transparency: Highlights where ideologies overlap and diverge.

Limitations

- Extremists May Appear Balanced: Leaders with extreme positions across all axes may appear “full” or comprehensive, masking their extremism.

- Subtlety Is Lost: Minor deviations may not stand out as much as large ones.

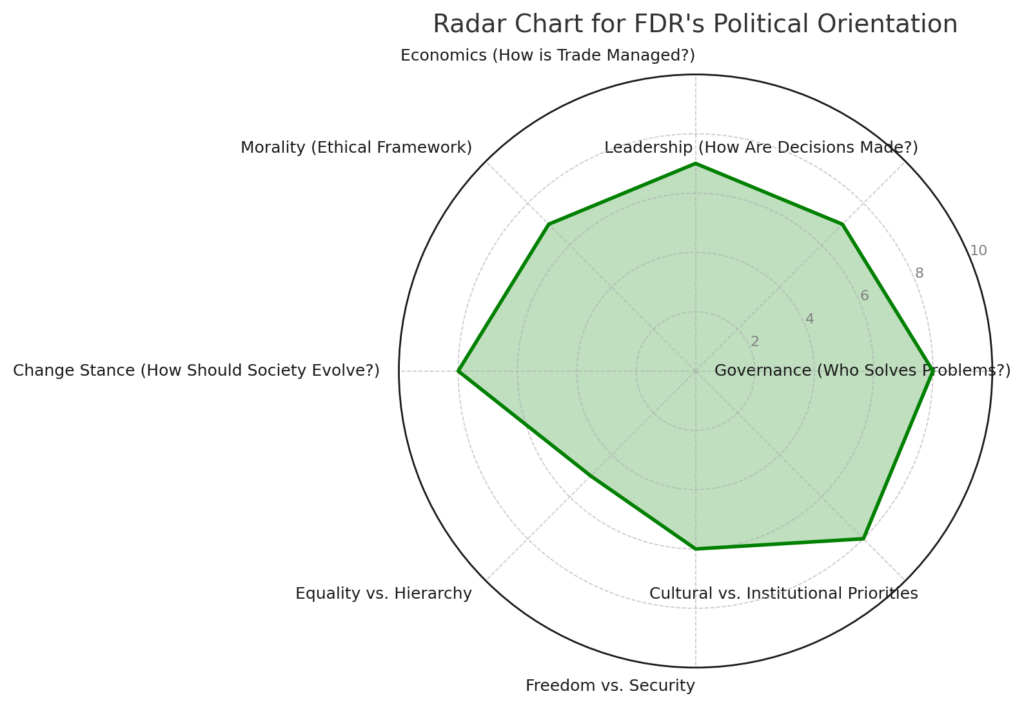

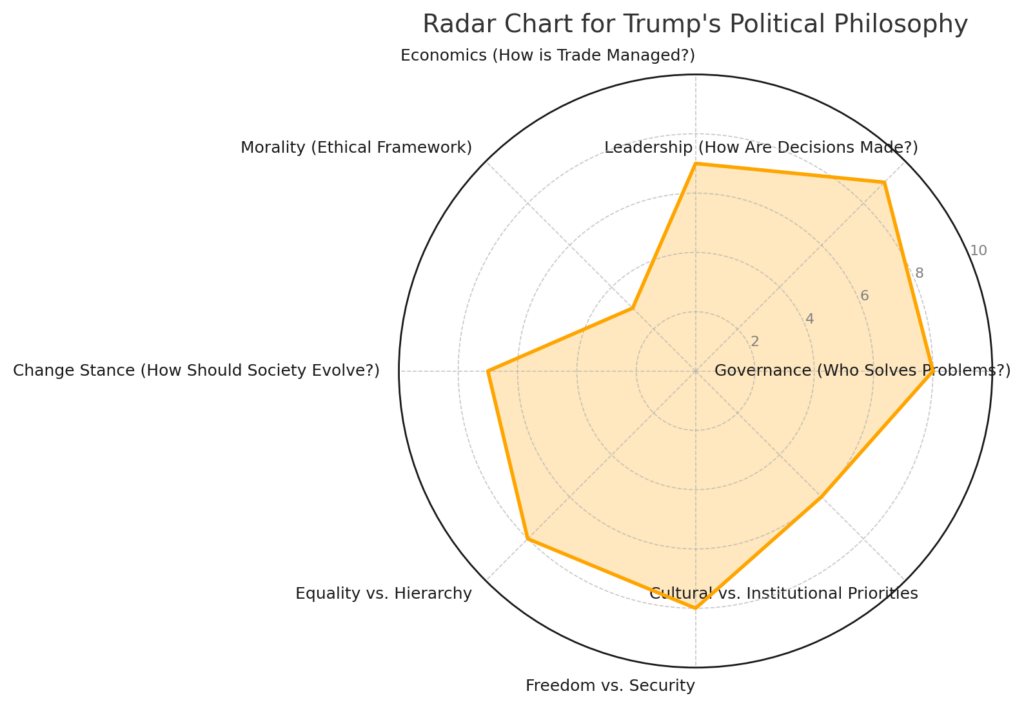

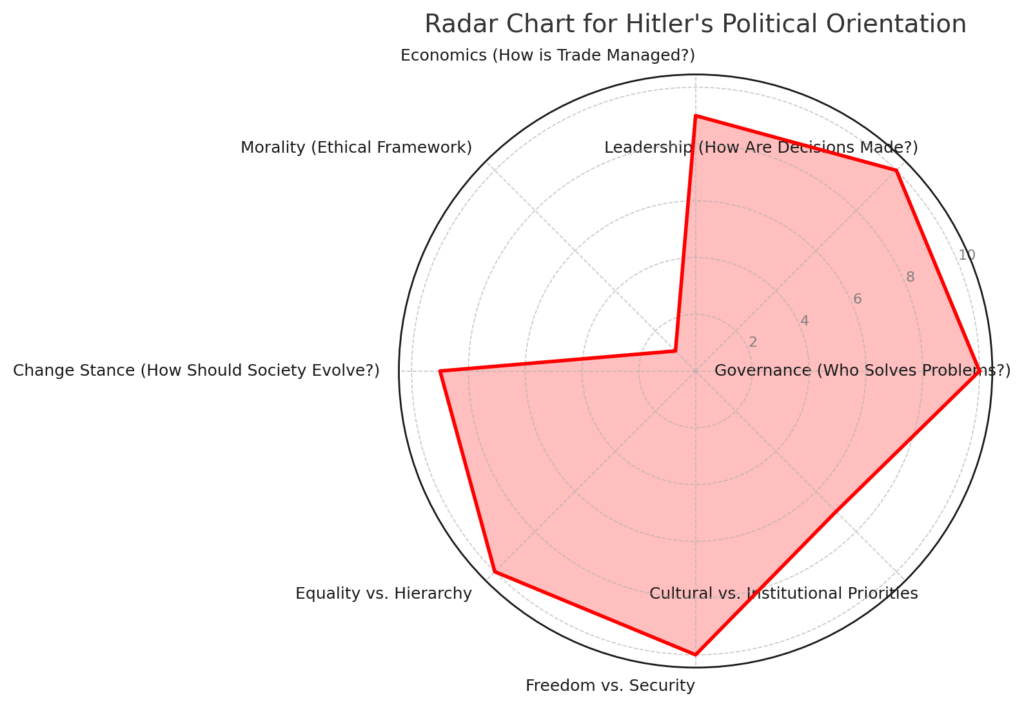

For example, plotting FDR, Trump, and Hitler reveals differences in their governance and leadership styles but also highlights how authoritarian figures can appear well-rounded due to their influence across many axes.

Refining the Model Will Take Adoption & Time

To address its limitations, I suggest the following improvements:

- Scaling for Extremism: Pinch extreme values to emphasize sharp spikes, showing authoritarian tendencies more clearly.

- Color Coding: Use green for balanced positions, yellow for moderate extremes, and red for radical extremes.

- Shape Metrics: Add quantifiable measures like “spikiness” (number of extreme points), “breadth” (coverage of axes), and “asymmetry” (balance between dimensions).

These refinements help distinguish between leaders with balanced ideologies (e.g., FDR) and those with dangerous extremes (e.g., Hitler).

How This Model Explains the Rise of Authoritarians

Alignment with Public Extremism

Even in peaceful societies, individuals often hold strong beliefs on one or two axes. Authoritarians exploit these shared extremisms:

- Governance Extremism: Promise strong, decisive action.

- Moral Extremism: Appeal to cultural or ethical values.

Consolidating Power

Authoritarian leaders score high on all axes, allowing them to:

- Present themselves as comprehensive solutions to societal problems.

- Fragment opposition by segmenting dissenting beliefs.

- Mask their authoritarian tendencies as strength or decisiveness.

Examples: FDR, Trump, Milei, and Hitler

FDR’s political ideology centered on progressive reform and federal governance, using centralized authority to address systemic issues like the Great Depression. His chart demonstrates balance, with strong but not extreme positions across governance, leadership, and institutional priorities. This even-handed approach allowed him to implement sweeping changes while maintaining public trust, demonstrating how centralized power can be wielded responsibly in times of crisis.

Trump’s political philosophy reflects a strong emphasis on leadership, governance, and hierarchy, with a populist appeal that resonated with those craving decisive action and traditional values. His chart shows a mix of authoritarian tendencies and pragmatism, with weaker emphasis on morality and institutional reform. This imbalance allowed him to rally specific segments of society while polarizing others, leveraging populism to consolidate power and amplify his influence.

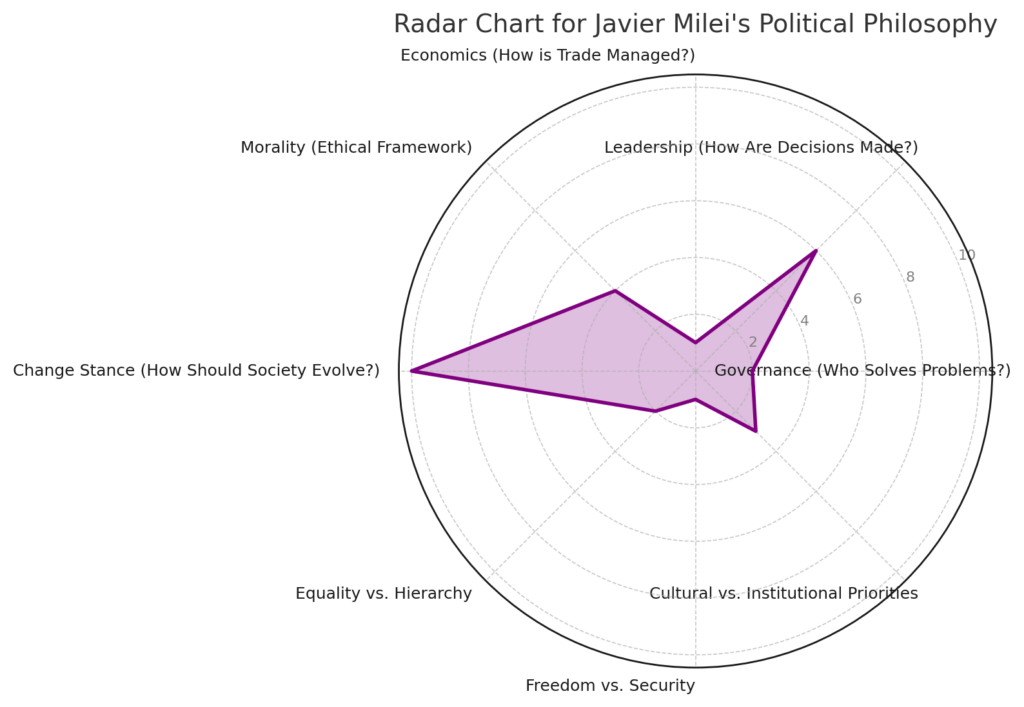

Milei’s chart reflects a narrow, radical libertarian philosophy focused almost exclusively on dismantling state control. His extreme positions on economic freedom and governance create sharp spikes, emphasizing his rejection of institutional authority and reliance on individual responsibility. However, his narrow focus on libertarian economics leaves little room for compromise, making him both a polarizing figure and a revolutionary force in Argentina’s political landscape.

Hitler’s extreme positions across governance, leadership, and hierarchy allowed him to unite factions of society while isolating opponents. His high scores across axes gave the illusion of balance, even as his extremism concentrated power in his hands.

Walking In The Spiderwebs

The left-right spectrum fails to capture the complexity of political ideologies, reducing nuanced positions into unhelpful binaries. By adopting a model based on multiple axes, we can better understand individual and societal beliefs, identify extremism, and recognize the dangers of authoritarianism before it’s too late.

This framework is not perfect, but it offers a clearer, more practical way to engage with politics. In a time when polarization and misinformation dominate discourse, tools like this are essential for fostering informed, balanced conversations about our future.